The life lessons of how to prune a tree

This is a short composition on pruning trees, written in a way that could be applied to one's life. I wrote it for my friend Vic Stanski in December 2021, as she is my open space for sharing these thoughts. Thank you Vic.

I recently helped my neighbors with pruning trees in parking strips in my neighborhood. These trees are among the most neglected, the ones next to the car, the ones that poke if you walk by, the ones that the delivery truck knocks its way through. In one case, it was on the far side of a corner lot and the people who lived in the house did not know the names of the trees or whether they should be paying attention to them. (In truth, on a previous weekend, some of us had quickly pulled up a bunch of the leaders on the lot, out of sympathy for the tree and the owner.)

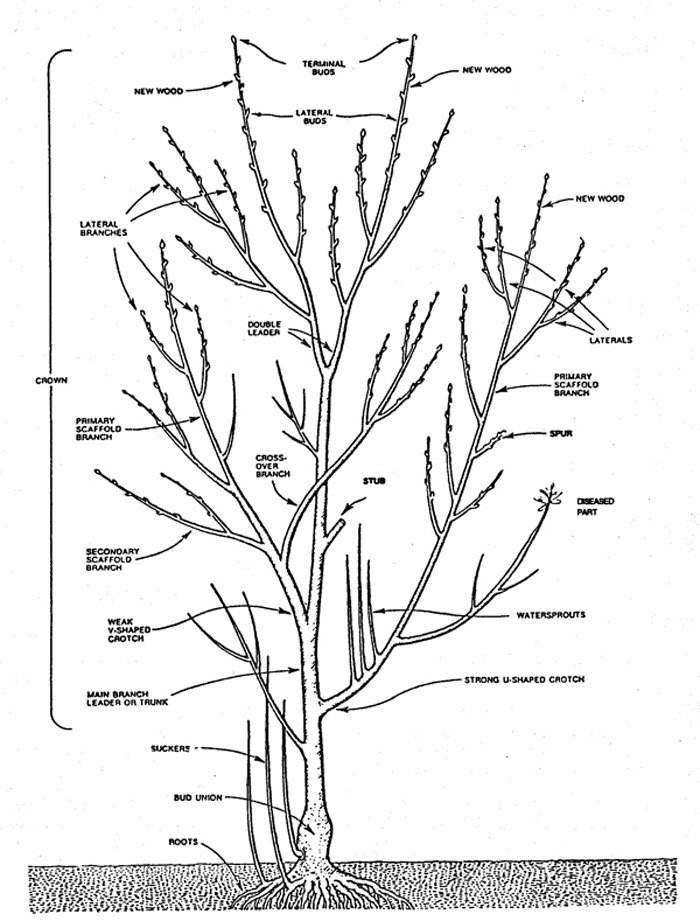

There is something called the habit of the tree. Or the aspect. This is understanding how the tree grows, if it is normal for it to spread in a certain way, how its canopy works, if it is vase-like in shape, if it shoots up with a strong central trunk, if it grows fast or slow, if it fruits. This innate pattern is important to understand first.

Before you cut anything, you look pretty hard at the tree. There is a lot of standing and pointing, a lot of thinking through the big moves and the must-have moves, to accommodate the budget. Because there is a limit to how much you can cut in a year. If you know you need to take out something big, you can't take out the small stuff. It is too much for the tree.

Maybe 50 to 80% of the time spent paying attention to the tree is looking, touching, stepping back, circling the tree.

Everything you cut, you put to the side of the tree before you put it away. You want to know what you cut. You want to be sure you stay under the limits: no more than 25% of a small tree in one year. That is the max.

Most trees have been hurt pretty badly already. They have been chopped off in strange ways, the trunk severed, anything growing into the street or the sidewalk cut at a bad point, so that there are spikes and other confused growth. These are puzzles. They cannot be fixed with a quick chop. They are multi-year healing processes. It might be as well to plant a whole new tree.

There is an order to pruning.

If you think of a tree as an energy budget, there are some features that you can take away without harming that budget. You can remove any dead and dying features, branches that are split in ways that will die shortly. These are places that promote infection and overall harm the tree's success.

You can also take away suckers. These are the shoots at the base of the tree or vertical shoots on a branch, which will send weight and pressure on the branch to break as it grows. These suckers, what a name, are pulling away at the main goal of the tree. Pruning suckers and dying branches does not count against your budget.

Then you look at the tree for what is growing successfully but doesn't serve the long-term goals of the tree. The first phase is codominant, looking for competing lead trunks. If the tree has too many leaders, it will be less successful. It is not the habit of trees to branch indeterminately, as a bush might; and yet we "top" trees in their youth, to stop them from their full height. This is against the nature of the tree. This is the priority for any pruner, take away the potential for competitors. Sometimes it means selecting the winner, based on light and space and potential and other branches. You can see now why so much careful consideration must be made before the first cut!

After that, things become less intense. For parking strip trees, you tend to focus on what will hit someone, what will ultimately be broken, either by you or by UPS. Breaking branches is bad for the tree, obviously, but sometimes the homeowners leave them in because they are beautiful or appear to be a nice branch, and then we end up snapping them at a poor point. So the pruners must take the proactive approach and be willing to make the cut early.

Crossing and rubbing, or C and R, are useful ways to look at whether the tree is growing outward or whether branches have been encouraged to grow inward, against one another, or take up space that is highly competitive for sun or for other possibilities. A tree that hasn't been pruned and has been through some rough adjustments will have many of these cuts.

There are many tools for cutting: saw, loppers, clippers. And there are special tactics for angles of cuts and where the cut occurs and how the tool you are using affects the angle. Blade toward the cut, always. We want to minimize the surface area of exposed wood, so that the wood heals well. We also cut above the collar, which if you look closely at a branch or any branching, is an evident clustering of cells that has a natural regenerative property. Cutting just above the collar means that the tree will heal well, curve back on itself and take care of the open wound.

You also must pay attention to the energy that the tree is pulling from the earth and pushing out to its very tips, and the energy that the tree earns from its leaves and brings back. Paying attention to these channels means thinking in a way similar to transportation, or streets and highways. You cannot have a highway that goes directly onto a neighborhood without some serious slow down, and traffic. Which creates other problems. So you must make sure that cuts accommodate all of the energy boosting up from the lane. Without that, sometimes you have a funny affect: a mad growth of small shoots trying to enact the extra energy. It can look wild!

The final properties we paid attention to were included branches, which means branches that grow too close to other branches. It is a funny one, because as you look you realize that most branches have a reasonable angle away from their origin branch. But some do not, almost like they have not decided to fully grow on a different angle. These bark points are very tight at the juncture, and they are dangerous for the tree in that structural integrity is difficult to maintain-- And both branches will fail. Cutting one of them early means that at least one will succeed.

The final look is spacing, aesthetics. This is where I feel most tender towards the tree, because it is a naturally beautiful thing, growing in its habit. This is where we pay attention to how the habit might flourish, and how we might encourage it. But this tender moment is short. We make our notes, we talk to the homeowner about their Japanese hornbeam, the Glorybower, the paperbark maple. We move on to the next before the sun goes down.