Fashion as Armor

Years ago, before the pandemic, there was a needed conversation about blazers in women’s professional fashion. It is a painful requirement in conformity, especially for curvy women. It does a job — makes you look like you belong. Of course, there are better blazers in women’s fashion. But in general, it acts as a costume. You put it on, you transform into a professional.

This is not close to pushing the limits of credibility. Read this article in Jezebel on the extended conversation on why aspiring female attorneys should wear skirt suits to lawfirm interviews (“Forget the Glass Ceiling, We Have Hemlines to Consider,” by Katie Baker in June 2012) >>

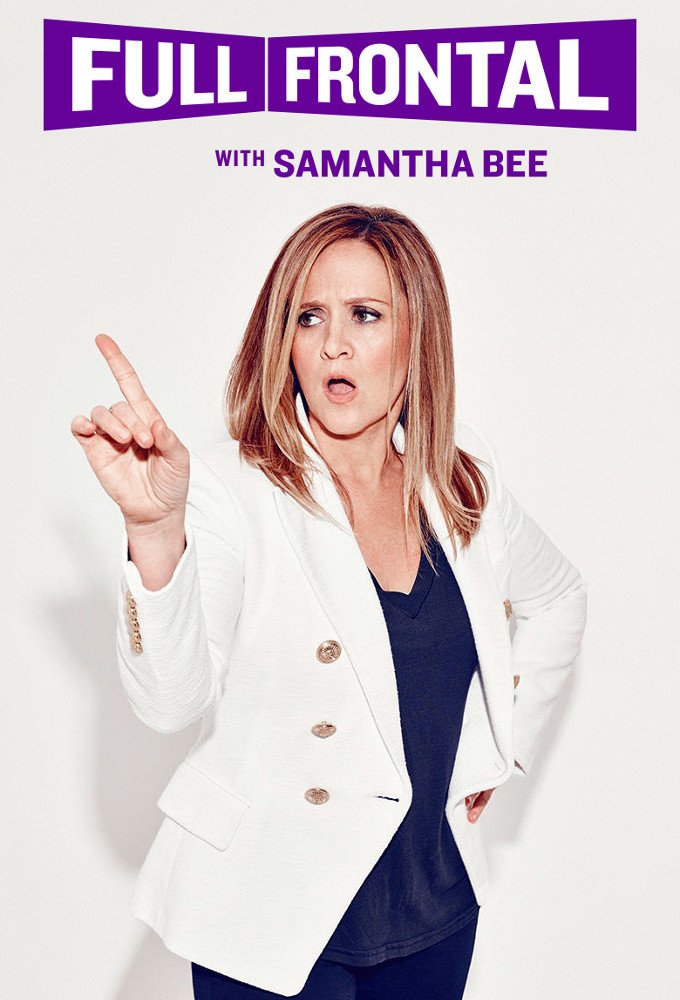

There are fantastic exceptions of women taking it to their own level, thanks to TV. Designing Women (shoulder pads!). Samantha Bee (velvet, white, killer).

My sister-in-law, a lawyer, called the blazer “armor.” Just as that professional transformation assured everyone that you belonged, it protected you.

Armor is a powerful idea. Today, picking up a surprisingly fantastic Allure magazine brought by hand to Costa Rica from the months of set-aside mail pile, I found an article about luchadoras, the subheading

“Makeup is armor for the women of Mexican wrestling.”

That means literal and figurative armor, for a female wrestler.

Browsing further in that same Allure, another feature: Laetitia Ky crafted her hair into silhouettes of a giraffe, boxing gloves.

Re-rendering your body as art: is there a more impressive way to use your appearance as a protection? (Image provided above as complete homage to Laetitia’s creations and the Allure editors who featured her.)

A memory: a same-age colleague of mine dressed impeccably, even as she worked for the state Deparment of Agriculture where perhaps it was not expected. Her point: careful dress is a way to show people you respect them, at the farm or in the office.

Another moment of recognition: the late Kobe Bryant, over a lunch in LA, instructing a young but failing NFL quarterback that he would never be an NFL quarterback if he didn’t look like one. Shave the crazy beard. Stop slouching. Show up for your teammates.

Respect and confidence, that is the real armor.

Below I share some of my and my brilliant sister-in-law Luisa’s musings in early 2017. A lifetime ago for both of us. For the record, she is a much better writer and more thoughtful feminist.

Black Blazer : Armor or Straightjacket?

For women in the workplace today, there is no shortage of advice and rules on how to dress. Women in the U.K. successfully fought an office dress code requirement for heels, while Kellyanne Conway famously told women that want more workplace respect to dress with "more femininity." Both were met with cheers.

So which is it?

In our experience - two mid-career women in contrasting professions - how women dress reflects the degree of respect they are afforded. We use clothes to convey importance first, and style if we are lucky. Business clothing norms stifle men too, sure, but being confined to a small closet of choices removes any uncertainty. Wear a cornflower blue shirt and no one will blink. Women can choose to stay in a well-traveled lane. But does that bring them more respect?

Take the black blazer.

Attending a technical conference, the small fraction of women participants may choose the black blazer as a familiar if fashion-tired way to blend in. Hopefully it fits, but for very few women does it flatter. That's not the point of wearing it. The point is to wear the uniform along with the men.

This is the "straightjacket" - the item that stops her from harming herself with questionable or distracting clothing choices.

For others, the black blazer is assurance. Wear the pink dress at the office, but when you go to the client meeting, throw on the black blazer. With one simple accessory, she now is transformed into a professional in her milieu. It is "armor." It makes her safe, secure, bulletproof. It justifies her seat at the table. She has joined the adults, she is wearing the uniform.

Or maybe, it is camouflage.

Another group of women-in-suits use the suit to break into male-dominated professions or gain economic advantage. Dressed for success in a man's world, they may or may not associate their appearance with a "cross"-identification of sex, gender, or desire; poor women at the turn of the nineteenth century, women in the 1970s struggling to break into "male" professions, and contemporary corporate women are a few examples.

The suit suits whom? Lesbian gender, female masculinity, and women-in-suits, by Lori Rofkin, in Femme/Butch: New Considerations of the Way We Want to Go, Michelle Gibson and Deborah Meem (Eds), Routledge, 2013, p. 167.

And what of the bodies that cannot be camouflaged? Whose shape is inescapably, loudly, 'feminine'? Let’s talk specifically about what it looks like, to wear a blazer, for these women.

Curvy bodies cannot be bound and tamed into the gentle slope required in the front for the lapels of the black blazer to lie fashionably flat (the fashion the male wearers of suits first defined). For these women, the singularly female flare of hips cannot be disguised by a longer line or a well-placed pocket. What about women whose bodies poke the suits at odd angles, interrupt the lines, pull at the stitches of a design that was never intended for them? They wear the uniform, but it doesn’t fit — telling its own story, its own code.

What if the armor is hurting the army?

It is well established that people who are overweight have more difficulty being hired, and are likely to be paid less. Do female bodies that are poorly matched to suiting initially designed to flatter the narrow-hipped, flat-chested, 6-foot man also run a similar risk of being considered less ...suited to the work environment they wish to occupy?

Well.

AUTHORS

Rebecca and Luisa are sisters-in-law. The former is a manager in a national laboratory and works in scientific enterprise and government; the latter is an attorney who works in Europe in international arbitration.